Highest Goal Scorer in Bundesliga: Who's Racing to the Top?

Section: Arts

Antimalarial drug resistance poses a significant challenge in the global fight against malaria, which continues to afflict over 250 million individuals annually and is responsible for more than 600,000 fatalities, primarily among children under five years old. Recent investigations conducted by researchers at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) have unveiled a critical mechanism by which malaria parasites absorb a human blood cell enzyme, potentially paving the way for novel antimalarial therapies. These findings, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shed light on how to engineer drugs that can more effectively combat this devastating disease.

Despite various treatments and preventative measures aimed at curbing malaria, the emergence of drug-resistant strains has complicated efforts. Although artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACT) have saved numerous lives, resistance to these treatments has been documented in regions of Southeast Asia and Africa, underscoring the urgent need for innovative therapeutic strategies.

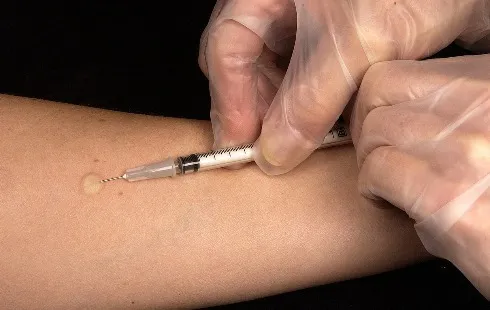

Many drug candidates fail during development due to inadequate absorption in the gastrointestinal tract or rapid elimination from the body. A promising strategy to enhance drug efficacy is the use of prodrugs, which are designed to improve pharmacokinetics and ensure targeted delivery to infected tissues. Prodrugs function similarly to a Trojan horse, allowing for a more precise attack on pathogens once they penetrate the necessary cellular barriers.

The research team at CHOP aimed to comprehend how antimalarial prodrugs are activated, focusing on identifying enzymes within the malaria parasites that could facilitate their activation, a crucial step for improving treatment outcomes.

Prodrugging presents an appealing approach as these compounds can bypass the protective membranes of parasites and host cells, while delivering an effective 'warhead' that targets and eliminates the parasite. The researchers discovered that a human enzyme known as acylpeptide hydrolase (APEH) plays a pivotal role in activating multiple antimalarial prodrugs categorized as lipophilic ester prodrugs. Although APEH is typically found in red blood cells, it is internalized by malaria parasites, where it retains its enzymatic activity, enhancing the effectiveness of these prodrugs.

This unexpected discovery has significant implications for future drug development. Mutations in prodrug-activating enzymes often lead to antimicrobial resistance, but since APEH is a host enzyme, it is less likely that the malaria parasite could evolve to resist prodrugs activated by it.

The researchers propose that harnessing an internalized host enzyme could lead to the design of prodrugs with enhanced resistance to the development of drug resistance. This advancement may allow for the creation of highly specific prodrugs targeting parasites or bacteria, reducing reliance on particular enzymes that can mutate.

Overall, this innovative research opens new avenues for tackling malaria, with the potential to develop more effective treatments that stand a better chance against emerging resistant strains.

Section: Arts

Section: Health

Section: Health

Section: News

Section: Arts

Section: News

Section: Travel

Section: News

Section: News

Section: Politics

Health Insurance in Germany is compulsory and sometimes complicated, not to mention expensive. As an expat, you are required to navigate this landscape within weeks of arriving, so check our FAQ on PKV. For our guide on resources and access to agents who can give you a competitive quote, try our PKV Cost comparison tool.

Germany is famous for its medical expertise and extensive number of hospitals and clinics. See this comprehensive directory of hospitals and clinics across the country, complete with links to their websites, addresses, contact info, and specializations/services.

The exhibition commemorates the 300th birthday of Kurfürst Karl Theodor, who became the ruler of Bavaria after the last altbayerische Wittelsbacher passed away in late 1777. Despite his significant contributions to economic modernization, social improvements, and cultural initiatives like the...

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!