How the Germans think of integration

A short history of Germany's immigration.

Before the Second World War, Germany was a country of emigration. Millions of Germans left their homeland especially bound for the United States. Later, there was some labour migration to the Ruhr area, where many Polish nationals from Eastern parts of the German Empire, but these migrants were German citizens. In Southern Germany, there were Italian workers in the Alps, but their numbers were not substantial.

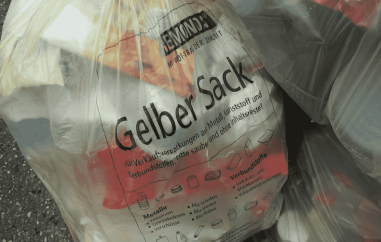

Migration really began on a grand scale in the 1950s when Germany needed a labour force for its postwar "Wirtschaftswunder" (economic miracle). First came the Italians, Yugoslavians and Spanish workers, and only later were the large waves of Turkish workers. Nearly everyone who arrived was offered a contract to work in the booming German industry, but never was this intended to become a program of migration. Originally, these so called "Gastarbeiter" (guest workers) were supposed to have returned to their home countries after an undetermined number of years. Only many years later did Germany become aware that most of these "guests" would be staying for good. The families of the original workers eventually followed them to Germany and by the 1970s the politicians were forced to face an unprecedented situation.

Unlike classical countries of immigration, such as the United States or France, Germany has a tradition that says citizenship is based on descent. During the Cold War, this made is possible for millions of German nationals in Poland, Romania and the Soviet Union to immigrate to Germany without the typical bureaucratic obstacles. On the other hand, foreign citizens born in Germany did not automatically become German citizens.

Only after 2000 was this law changed, and today anyone born on German soil has the right to German citizenship. The only stipulation is that each person has to choose only one passport. Although the option of having double citizenship with dual passports has some political support it is simply no longer available.

Because of this history of citizenship based on descendancy, it still not common in the minds of many Germans that one can be German even if the person does not look stereotypically German or have a German sounding surname. For example, they are often asked where they came from, even if they have lived here for three generations. To the outsider, this might look as if it is a matter of xenophobia or racism, but in nearly all cases this is inaccurate.

The intellectuals and the politicians can clearly see the benefits of integration. Some have attempted to promote better planning and implementation, but it takes a long time to convince the average citizen. Anything like this, which has such historical roots, takes not years or even decades to change but rather generations.